Edge Pieces and Corners: Building My Family History

When I moved to the US in 1995, I naively thought of myself as a bold adventurer, the first in my family to venture overseas. When DNA testing became a thing, I very quickly realized that I have a lot of distant cousins here. Back then, the tools to help you join the dots and determine the who, how, and why distant relatives had made the journey across the Atlantic didn’t really exist, but I’m happy to report that that is starting to change

Every 12-18 months, I find myself diving deep into genealogy… a bit too deep sometimes, as I find myself getting burned out, and end up putting things on the back burner for another year or so. Recently, I signed up again for Ancestry.com, and I’ve been doing my best to pace myself. Today, I decided to try one of those new technologies they’ve added since my last deep dive, which is called Thrulines. What it does is use Ancestry family trees to suggest how you might be related to your DNA matches. It works backwards, starting with your parents, to show you how you might be related to your DNA matches through ancestors you share. Basically, when it finds people that have matching DNA, it looks to see if you have common ancestors in your respective family trees.

I didn’t find any Thrulines until I went back to my great-great-grandparents, where Ancestry had identified 17 potential matches. I decided to explore the DNA matches they’d found through my great-great-grandmother, Sarah Stone. Sarah was born in 1828, in a small Derbyshire village called Heage, which is less than 10 miles from where I grew up.

As I sifted through the available facts (births, baptisms, marriages, and all too soon deaths), I started to see just how hard life was back then. Sarah was the youngest of three children, and was only four when her mother Mary Stone (née Clark) died. Less than seven months later her father (James Stone) remarried, and went on to have a further eleven children with his second wife Polyxena Stone (née Jepson). Of her two full siblings, her sister Mary Ann Stone died at the age of 24, and we will be returning to her older brother Joseph E. Stone (1822-1899) later.

After the death of her mother, the next time Sarah turns up in the records is in the 1851 census, when she was living with her 80-year-old grandfather, Richard Clark. A few months later she married her first husband Charles Garton (1831-1857), and they had one daughter together (Mary Ann Garton), before his death in 1857, at the age of 26. Sarah remarried two years later, and this time it was to my great-great-grandfather John Richardson (1832-1909), and they went on to have a further six children, including my great-grandmother Sarah Richardson (1867-1918), who married my great-grandfather George Ford (1865-1902).

Okay, it’s time to return to my great-great-grand uncle, Joseph E. Stone, and why I’m so fascinated to dig into his branch of the family. The reason is that just a few weeks after marrying his wife Elizabeth in early 1845 (in the village church where my parents were married and are now buried, and where I was christened), he and his bride arrived in Ellis Island to start a new life in America. Interestingly, they arrived 150 years before I did, settling in New Castle, Pennsylvania, whereas I arrived in 1995, settling in a different New Castle, 100 miles away in Delaware.

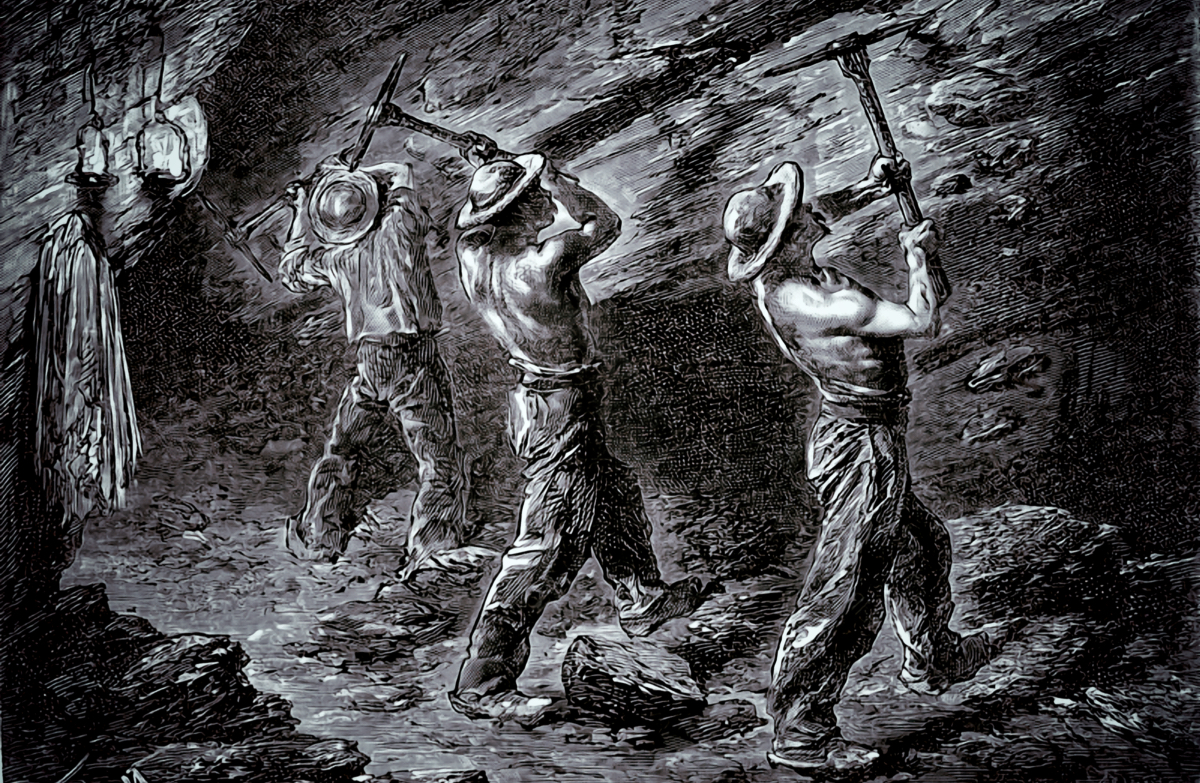

As I’ve learned more about my family history, many of my male ancestors over the last 250 years were miners. As I’ve dug into the details, I’ve seen migration patterns play out in my family tree, as new, richer coal fields were discovered and exploited. When deeper coal seams were discovered around Nottingham in the 1920s, my grandfather moved his young family there. As miners were paid based on the amount and quality of coal extracted, they would move to where they could earn more.

I didn’t really know much about US mining history, but it seems that large deposits of anthracite coal had first been discovered in the mid-18th century, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the Schuylkill Canal in 1822 and then the Reading Railroad in 1842 that the boom really began. Joseph and Elizabeth made their lives there, going on to have nine children together. In 1863, he was drafted into the Union Army, fighting in the Civil War, before returning to the mines. Despite that, I’m guessing life proved easier in the US, as three of his younger half-sisters also ended up migrating across the Atlantic. I am still researching their stories, but for now, I’m happy to finally be assembling some of the puzzle pieces that explain why I have so many DNA matches here in the US. Keeping with that analogy, it feels that I’ve really started to put together all of the edge pieces and corners, and that gives me a solid framework to explore further.

My takeaway is that genealogy can bring history to life in a way that books and other forms of media cannot. It’s that combination of the big things (wars, plagues, colonization, etc.) and the way that they play out in the everyday lives of generations of our families. Coming from a mining family, I’ve seen the lives of far too many branches of my family impacted by mining-related deaths and disease. Families will appear to be thriving in one census, and then ten years later they will have been scattered to the winds, with children as young as 11 working in factories or as servants, widows living out their lives in workhouses, and younger children being taken in by other parts of the family.

I already knew that mining had so much impact on my family over the last 200+ years, but I hadn’t really stopped to consider how mining (and to a lesser extent the railways) had led some of my distant relatives to take their chances overseas. The more I learn about my ancestors, the more I appreciate the sacrifices they made and the resilience they showed. They weren’t just names on a page; they were real people who made choices that shaped the course of my family’s history.

What I find fascinating is that I spent the first 27 years of my time here in the US within a couple of hours. I remember visiting Jim Thorpe for the first time, which is a town in eastern Pennsylvania with a lot of coal mining history. There was something about it that felt like ‘home’, and I assumed that it was because former mining communities feel similar, because they were built by hardy, resilient people. Jim Thorpe is 30 miles from where ‘Uncle Joe’ made his life, and where he and Elizabeth are buried. Now I’m thinking that maybe it felt familiar, because distant cousins lived and worked there.