Life in a Northern town

As the youngest of 3 boys, I grew up in an environment where education was seen as the key that unlocked everything. It wasn’t a matter of if I’d go to University (that was a given) but whether I would follow in the footsteps of my two older brothers and read Physics at Westfield College, which is part of the University of London. If it sounds like it was a family tradition, it was a relatively new one. Both of my parents came from impoverished backgrounds, with neither of them staying in school beyond the age of 15, or ever taking any public exams. My dad used to tell the story about how he’d been singled out for his abilities at school, passing the scholarship test, only to be told that was no money for him to stay on at school, and that he’d be joining his dad ‘down the pit’.

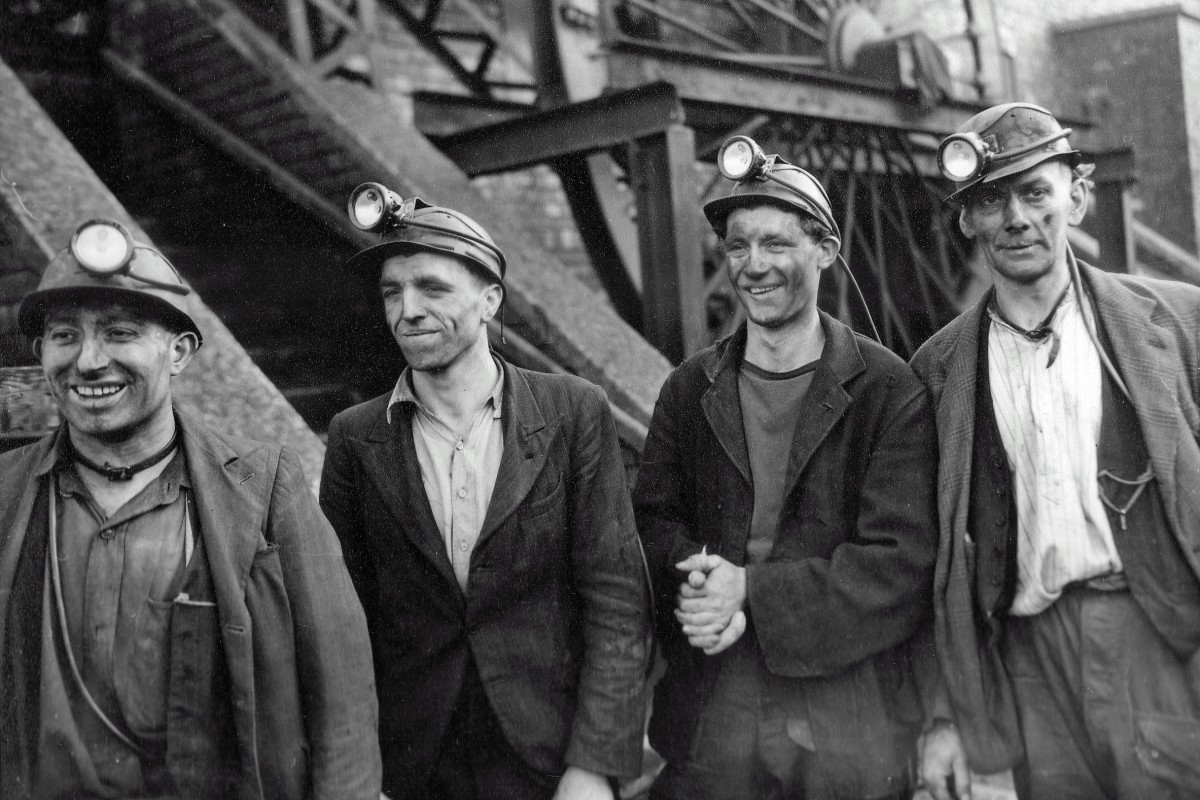

Both my parents were children of miners (as were their dads, and their dads before them, as far back as the records go), and both grew up in extreme poverty. For my dad, it was because his father, while hardworking, was a drunkard, a gambler, a bully and a womanizer. What we now know as domestic violence was known as the ‘blue devils’ back then, or it least it was in the part of the world where I grew up. According to Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary, blue devils is acute delirium caused by alcohol poisoning [syn: delirium tremens, DTs] or a fit of despondency. In far too many homes of the 1930s, it probably played out the way it did in my dad’s childhood home. His father would drink and gamble away most of his wages before he ever got home, and then when his wife asked him for housekeeping money, he’d beat her, often in front of their children.

By the time my dad was 15, he was already working down the mines, which had turned him from boy to man. He decided that it was time that someone stood up to his dad, and as the oldest of five children, it was up to him. He stepped in to protect his mum, and as a result, he was severely beaten and thrown out on to the street. It was after midnight, and he had nowhere to go. He decided to see if his aunt would take him in, and started walking. She still lived in the village where my father was born, which was 20 miles away. It took him 6 hours, and it was morning by the time he arrived. I remember my dad first telling me this story, with my response being to think warm thoughts of the aunt that took him in. I said something to that effect. My dad told me that she hadn’t been all that warm-hearted; that she wouldn’t let him into the house until he promised that he’d go to the local pit that day, and get taken on. He did, accepting one of the most dangerous jobs in the mine, as the person who put in the pit props (large pieces of lumber used to prop up the roofs of tunnels) as new coal seams were opened up. He said that her condition for letting him live there was that he’d turn over his pay packet at the end of the week, and that she’d give him spending money back. It sounds to me like she’d probably learned from her own mother’s and sister’s experiences.

Over the years, I’ve made three different attempts at documenting my family tree. The first was in the mid-1970’s, when the easiest way was to put in a personal appearance at St. Catherine’s House, where records of all UK births, marriages and deaths from 1837 onwards were then kept. You’d look up the individual in the relevant card index, fill in a form requesting a copy of the relevant document, pay your fee and wait while someone retrieved the document and made a photocopy for you. It was a painstakingly laborious process, but I was young, had time on my hands (I was staying with my brothers in London for a couple of weeks during the summer holidays) and was caught up in the romance of discovering long-forgotten ancestors.

As I mentioned earlier, what I discovered was that I come from a very, very long line of miners. No matter which way I traversed my family tree (mother’s mother, mother’s father’s mother, father’s mother, father’s father’s mother, etc.), every male of working age was classified as ‘miner’. Every single father and every single husband, with every single son destined to join them, until my very own generation. What I discovered next was that as a family, we didn’t get about very much. As I went back through the generations, I never found anyone that had been born, married or died further than 25 miles from where I was born, and for the vast majority, it was less than 5 miles.

The other thing that I discovered that day was that mining is neither conducive to good health or long life. As I went through the death certificates, I found that the majority of my forefathers had died young, and usually from mining-related illnesses, with pneumoconiosis or black lung being among the most common causes of death. All too often, the cause of death recorded hid the story of what had actually killed them. As I think back to my childhood, many of the men in our village, and in the surrounding villages and towns were, or had previously been, miners. While most of the local mines closed in the early to mid 60s (there used to be five pits within a couple of miles radius from where I grew up), many miners were bussed to mines 20 or 30 miles away. As I think back, I struggle to remember the few elderly men within the community, and those that I do remember, would usually be prematurely aged, stooped low and gasping for breath.

My mother’s father was a casualty of the mining industry, but not in a way that showed up on his death certificate. The earliest picture of him that I have shows him as a fresh-faced boy soldier in the Second Boer War (1899-1902). I have a second picture which show him in his WW1 uniform. He’s older, probably wiser, and still looks very strong. I know that he was gassed in the trenches in 1917 or 1918, and was invalided out of the army. Once his health recovered, he went back down the pit. The next picture that I have shows him bandaged and leaning heavily on crutches. He broke his back in a mining accident in the mid-30s, and doctors said that it was a miracle that he survived. As it was, he never worked again, and never really walked again. His bed was moved downstairs to the front room (my cousin tells a story of her earliest memory being of going to visit him, and being taken into the darkened room) and he died in 1947.

Like my dad, my mum was very bright, but staying on at school wasn’t an option. With her dad being an invalid, she needed to get a job as soon as possible. At 14, she left school, joining my grandmother working in the canteen at the local ironworks.

Who knows what my parents would have achieved, had they had the opportunities that they gave to us? As it was, they both worked hard and did well. They had good fortune early in their married life, when my dad was one of four miners that won the football pools (the National Lottery of the time). They’d correctly forecasted eight football matches that resulted in score draws, netting them the maximum 24 points possible. There were no other winners that weekend, and the payout was a world record of almost £76,000, or £19,000 each. That was in 1952, and that would be equivalent to winning £1.4MM (or $2.2MM) each.

My parents were incredibly generous with their new-found wealth. In addition to building a new home for themselves, they bought a house for my grandmother, and gave generous sums to each of my mother’s siblings. My dad continued working as a miner for another 2 years, before deciding to leave the mines for good. They bought themselves a small shop, where my father worked while my mum raised my brothers, and then a few years later, found herself raising me. As supermarkets were introduced to the UK, it became hard to compete, and my dad applied the “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” adage, going to work for one of his new competitors.

As a young child, the family aspiration for us to go to college was supported by the small primary school that we all attended. When I reached the age of 11, that changed dramatically when I headed off to secondary school. All along, the assumption had been that I would attend the same grammar school as my brothers had. In my final year, the UK education system changed dramatically, with the comprehensive system replacing grammar schools in the majority of the country. Courtesy of an arbitrarily-drawn catchment area, I found myself attending one of the roughest schools in the area. Had I lived a mile away (or had my middle brother not headed off to University the year before, meaning that I couldn’t take advantage of the one-year ‘elder sibling’ proviso), I would have been able to attend the school of my choice.

I very clearly remember an incident from my first week there, which was to set the tone for the next five years. The teacher stood at the front of the class, and asked us to go around the room, saying what we wanted to do when we grew up. I was one of the last to go, and had listened as child after child had said “go down the pit”, “work in a bank”, “work in a shop”, etc. I had no idea of the ensuing shit-storm that would hit my life when I proudly announced that I planned to go to University and then become a scientist. There was silence for a moment, then laughter, then ridicule. The teacher, missing his moment to stop it before it got out of hand, decided to endear himself to his new pupils by joining in.

A little part of me died that day.

The bullying started that day too, and continued for the next five years. I was mocked, ridiculed, laughed at, ignored. I was picked on, taunted, made the butt of all jokes. I was tripped, pushed, kicked, punched, slapped. I had my belongings stolen, damaged, defaced, destroyed. For the first year, I used to live in fear of the end of the school day, because that meant that I’d have to face the gangs that were waiting for me outside school.

One day that all changed, but that as they say, is another story for another day.

© Robert Ford 2012