No need to put on that red light

Back in 1972, when the decision to scrap the 11-plus exam in Derbyshire was implemented, Deincourt School was woefully unprepared to become a comprehensive. It didn’t have the facilities, the staff, the books, the curriculum, and most importantly, it didn’t have the culture or the mindset to educate kids of all of abilities. Of course, lots of promises were made at the time, and so people generally went along with it, hoping for the best.

One of the challenges that emerged when it got time to choose our options (the subjects that we would study for two years, leading up to exams when we were 16), was that there were two distinct sets of qualifications; CSEs (Certificate of Secondary Education) and O-level (General Certificate of Education: Ordinary Level). Nowadays they have been replaced by a single academic qualification, known as GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education). While the previous CSEs and O-levels were supposed to cover the full spectrum of abilities (CSE grade 1 was recognized as being equivalent to a ‘C’ at O-level), in practice, the curricula could be very different.

Just to throw an extra level of complexity into things, for O-levels, the school could choose to adopt curricula from different Examining Boards, which could be very different, from a content perspective. Sometimes, they’d choose a particular Examining Board, because the perception was that it was easier for students to get good grades. At other times, teachers would select a curriculum that was more in line with what they’d studied in a different part of the country. While that might be good for them, it wasn’t always good for the students, particularly if those were going to go on to to do A-levels, which were designed to reinforce and build upon those earlier studies.

For me, I went on to study Maths, Physics and Chemistry at A-level, after going on to Tupton Hall for Sixth Form, and there was a disconnect between each and every one of those subjects, between the curricula I’d studied at O-level, to what I was now trying to study at A-level. While I expect that lots of other schools were experiencing the same sort of problems at that time (the introduction of the comprehensive system was a pretty big and messy deal back then), Deincourt seemed particularly unprepared to handle the sort of challenges that came up.

The origins of the story I’d like to share is a prime example of the short-termist and atomistic thinking (as opposed to holistic thinking) that would pass for strategic staffing at the school. If I think back to my third year at Deincourt (the year where you choose the subjects that you will study for your final two years), one of the highlights was that being in the top class, we had the Head of Science taking us for General Science. He was a particularly good teacher, and just brought the broad spectrum of science to life for his students. It turns out that he was also ambitious, and keen to move on from Deincourt. As we contemplated our options, he would be the one teaching Physics. Both of my older brothers had studied Physics at the University of London, and being keen to follow in their footsteps (just like footsteps in the snow, it is always to easier follow where someone else has lead), I was really excited to choose Physics as one of my subjects.

As Year 4 got underway, we learned that our Physics teacher was getting close to completing his degree through the Open University. Like many of the teachers there, he had a teaching certificate, but no degree. I remember us all being supportive when he told us that his finals were coming up. What we didn’t realize was that as soon as he graduated, he would get a new position at a local Technical College, and tender his resignation, planning to leave at the end of the Easter term.

Around that time, I was captain of the school chess club, and because we were doing well in the Sunday Times chess competition that year, our headmaster would often accompany us to away games. I played first board, and my game would often be over pretty quickly, and so he’d look to engage me in conversation. I hated him with a passion, but for some reason, he would share some of his decisions with me, even though I was someone who was directly impacted by them. On one particular occasion, he decided to share his rationale for not directly replacing our physics teacher. Apparently, he hadn’t liked any of the candidates with relevant experience in teaching physics, but had become enamored with a candidate who taught biology. His decision was to hire that person, and then have one of the games teachers backfill on teaching physics. Yes, dear readers, you read that correctly. He hired a biology teacher that the school didn’t need, and asked a games teacher with no knowledge of physics beyond O-level to teach… well, to teach o-level physics.

So, as the final term started, there was some trepidation on my part, as to how our Physics class would turn out. While the games teacher was a very popular guy, particularly for the kids who were into sports, it very quickly became clear that he knew nothing about physics. We found ourselves going back over topics that we’d already covered, such as optics and light. It turned out that the reason for that was that he was a keen amateur photographer, and so that was an area that he felt comfortable teaching.

As we learned about his love of photography and took an interest, he became keen to teach us more about that, and offered to teach a few of us what he knew. Between the physics and biology labs, we had a darkroom that we’d never really been aware of. It turned out that this had long been his domain, and he was now willing to share it with us. Maybe physics wouldn’t be so bad, after all?

For the next couple of weeks, he’d load up a couple of old SLR cameras with black & white film, and he’d encourage us to go out and practice our camera skills. He’d then schedule for us to meet him in the darkroom the following day, where he taught us all about developing film and printmaking. For the first couple of times, he stayed with us, but he felt confident that we knew what we were doing, he left us to it. We’d heard rumours that he was dating one of the other teachers, and so we all decided that he probably wanted to hang out with her in the staff room.

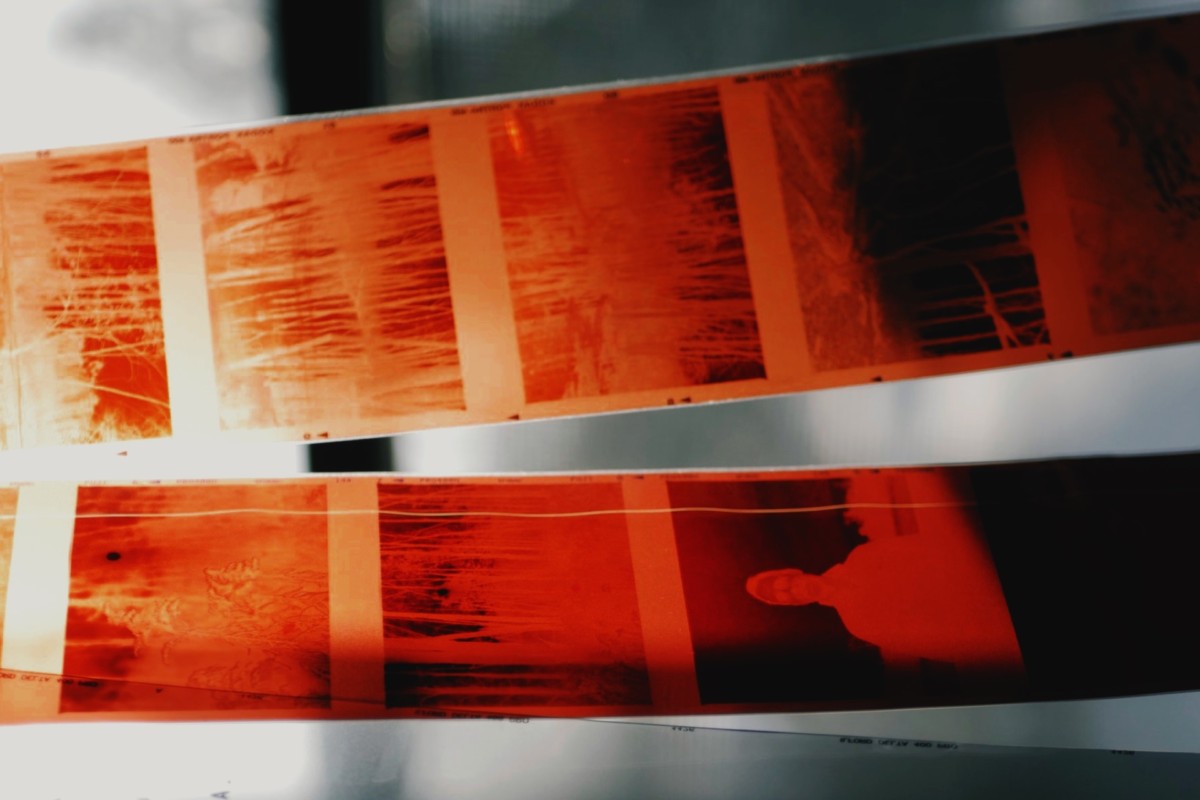

On the final day that we were allowed into the darkroom, everything seemed as normal. There were 4 or 5 of us crammed in there, and we were wanting to develop and print some shots that we’d taken earlier. One of our group was a little less interested in the process than the rest of us, so he was spending his time rifling through all of the drawers and shelves that lined the end wall of the darkroom. No-one was paying any particular attention when he started holding up some negative that he’d found to the light, until he said “there’s a nude woman on here”. That is when he got all of our attention. Suddenly, we all wanted to look at the negatives, and I seem to remember that we all grabbed a film strip from him, and held them up to the light. Yes, those were definitely pictures of a nude woman. For those of you who have only ever known digital cameras, a film negative wasn’t very big (standard 35mm film measures 24mm x 36mm, or about 1 inch x 1.5 inches), and it was a negative image (with the lightest areas of the photographed subject appearing the darkest and the darkest areas appearing lightest).

There was only one thing to do (or at least to 15 year-old boys, there was only one thing to do), and that was to create some prints. We all crowded around as we first exposed the image on to photographic paper, and set about developing it. I’d always loved how when you dipped the the photographic paper into the developer solution, you’d slowly see the image emerge. You’d ‘fix’ the print and wash it thoroughly, and only then, really inspect the image that you’d created. This time, the process became much more frenzied, particularly when we realized that the person that was being revealed to us was none other than the female teacher that we’d heard rumours about, in all her birthday glory.

There was a pause, where I think all of us were contemplating the reality of the situation, that we’d seen things that we shouldn’t have seen, and knew things that we had no business knowing. That was quickly broken when one of us said “I want a copy of that”, and then someone else added “let’s make enlargements”. In the next 20 minutes or so, we created an impromptu production line, and we printed approximately 25-30 8″x11″ prints from two of our favorite shots. What we quickly learned, and what ultimately become our downfall, was the bottleneck of the drying process. The photo dryer was a large metal plate that was heated from beneath. You would put the prints onto the plate, and then lower a fabric cover over the top. This would help speed up the drying process, and ensure that the prints dried flat. Unfortunately, it would only fit two enlargements at a time, and had a cycle time of a few minutes, resulting in us having a backlog of dripping prints, all waiting to be dried.

It was around that point that we heard a knock on the door, and a rustle of the doorknob, as the games teacher tried to enter into the darkroom. Thankfully, we’d remembered to lock the door. “Let me in, lads”, we heard him say. We all looked at each other, in a state of utter panic, until some bright spark shouted out “we can’t, sir… we’re just doing some developing”, while simultaneously hitting the light switch which turned on the both the darkroom’s red light, turned off the regular light, and lit a red bulb outside the darkroom.

Picture the scene. There are 4 or 5 panicking boys, who are convinced that they are about to be busted. There is an impatient games teacher, directly outside the door, who is saying “hurry up, lads… lunchtime is almost over”, and repeatedly trying the door. The room is bathed in red light, which makes it hard to see, and there is a lot (and I mean A LOT) of incriminating evidence, everywhere. We hurriedly start to cover our tracks, putting the negatives back where we found them, putting the dried prints into our bags, making sure that we took any scrapped prints with us. At the end, in a seeming act of desperation, we were even stuffing the wet prints under out sweaters. We even remembered to take the last print from the print dryer. Finally, and pretty shakily, we switched the regular light back on, opened the door and sheepishly headed off to our form rooms for registration.

Word tends to get out pretty quickly in schools, and so by the next day, there was a lot of buzz about what we’d found, and people were coming up to us in the playground, asking if it was true. My response was to channel my inner Sergeant Schulz (from the TV show ‘Hogan’s Heroes’), and say “I know nothing”. The next day, we had a Physics lesson, which I was dreading, as I was convinced that the games teacher must know by now. It started off relatively normally, which lulled me into a sense of false security. At some point, he asked me to go and get something from the Biology classroom, which meant that I had to go past the darkroom. What I didn’t realize was that he followed me, and as I drew level with the darkroom, he grabbed me and bounced me off the opposite wall, He was holding on to my blazer by the lapels, and he brought his face very close to mine. I could see the rage in his face, and how he was fighting to control it. He leaned in closer, saying “you are banned from photography… you are banned from the darkroom… you are banned from being in the science block outside of your lessons… you’re lucky that I don’t kick you out of my class… now get out of my sight”, before pushing me in the direction of the Physics classroom.

It turned out that each and every one of us had a similar confrontation with the teacher. It also turned out htat how we’d been busted was that when we retrieved what we thought was the final print off the print dryer, there had actually been two on there, but the other one had stuck to the fabric cover, when it was lifted up. For my final year, physics lessons were something that I dreaded, because he would always be looking at me with that “I know what you did” look in his eyes.

Now, as an adult, I realize the sheer stupidity of what he’d done, and how he and his partner must have both feared that they might lose their jobs, if word got out of what we found. Over the years, I’ve occasionally caught up with my fellow photography enthusiasts / conspirators, and we’ve laughed as we recalled that day. Those two minutes of utter panic were really something like a scene from the Keystone Kops!